|

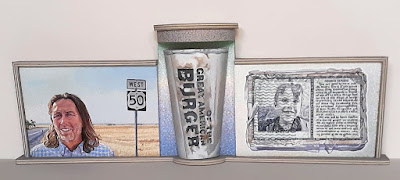

54 Sky Panels from Holden to Sevier Lake, Utah, US Highway 50, 2014-2017

acrylic on 54 panels, artist-made frames, 51 3/8 x 77 7/8 x 1 3/8 inches

Courtesy of Valley House Gallery & Sculpture Garden

|

|

Left side view of 54 Sky Panels from Holden to Sevier Lake,Utah,

US Highway 50, Courtesy of Valley House Gallery & Sculpture Garden |

A favorite painting of mine, is divided up into a grid of

450 squares. It certainly did not begin that way. When first painted, I was

living in Richardson, a suburb north of Dallas, Texas. In the tiny apartment,

there was no space to paint anything of scale. A small kitchen table, that

couldn’t possibly fit in the minuscule kitchen, doubled as a studio. On the

other side of the elevated railroad tracks, which ran behind the block of nondescript

brick apartment buildings, there was an empty field. That is where I’d go to

work on large projects. Sometimes while working outside, I’d draw a small

audience of kids, usually arriving on bicycles. Although, I always tried to answer

their questions directly, it was never that easy trying to explain abstraction

while painting.

When the weather was pleasant, I’d search for a section of

beaten down weeds, as far away from the street as I could find, and lay some raw

canvas on the ground. The resistant stubble of wild plants, felt nothing like

the smooth studio walls that backed the stapled expanses of canvas that I

painted on in college. On the ground, the fabric was never flat. The pressure

of the brush against the debris underneath, left impressions in the paint

similar to rubbings made with crayon on paper. Brushstrokes lack a sense of

calligraphic weight when trying to glide over a rumple of woven ridges.

Abstraction in the field, quickly moved from Franz Kline like gestures, to

gravity centric acts, which were more in line with the layered constellations

of Jackson Pollock. While flinging paint from the end of the brush, I also

dumped large quantities of white onto the fabric. Stepping into the puddles, I began

kicking the paint around, leaving the imprint of my shoes as part of the

overall imagery. Into those impressions, I poured a watery mix of pigment and

let it run all over the canvas. I liked the result, but it always felt like

there was something missing.

While attending the University of Nevada in Reno, I saw a

canvas covered with a grid of graphite lines. Agnes Martin had carefully

painted the spaces in between with white. The simplicity was striking. It reminded

me of the shimmer of reflected sky on the side of glass buildings. While attending

the university, my parents moved to Dallas. Visiting them on a Christmas break,

we circled the city as the sun began to set. Within a cold yellow sky, glass high-rises

burned like hot coals on a circular horizon. I remember distinctly feeling that

I’d never seen anything quite like that before.

When I moved seven years later to El Paso, Texas, I had

another go at it. This time, I overlaid the embedded footprints and splatters of

paint with a graphite grid of squares. While it broke some of the dead areas up,

it still didn’t get me there.

A couple years after that, I move to Fillmore, Utah. One day

while looking at the painting, I decided that the grid needed to be more

physically defined. I had an old painting from college that I never entirely

liked. Composed primarily of pinks and blues, I thought it was a little too

pretty. I decided to cut it up into squares. Back then, I frequently painted

into wet gesso and raw canvas and watched the pigments bleed into the cream

colored fabric. Subtle patterns happened on the back side of the canvas where

it had been stuck and stapled to the wall. With all the pieces piled in the

middle of the floor, I randomly began to glue them into the grid of the field

painting. Some pieces remained face up, while others were turned upside down.

As I did this, I intentionally left many of the spaces blank so as not to conceal

all of the embedded footprints. The grid became a combination of three paintings

because both sides of the cut up canvas were applied to the original artwork.

What I was looking for was a kind of randomness. To reinforce that, I traced

the grid with linear beads of glue. Into those wet ridges, I pressed a couple

different colors of sand. When the mortar like lines dried, I had a restrained

mosaic of graphic atmospheric squares.

I always enjoyed the randomness that inhabits nature.

Because nature was a better designer than I could ever be, composition was

never an obsession. I just went with what I saw, knowing that I could never

improve reality. When I began thinking about the sky panels, I wanted to take

the randomness I saw on walks and apply it to the sky. Of course, sky already has

an ambiguity that I could never match, it’s just that the blue skies of beyond,

are never equated with the splendor of lowly weeds or erosion. Yes, I said it.

Weeds are absolutely beautiful!

One day, on the way to the mailbox, the light in the sky was

exceptional. Studying the mosaic of canvas squares, I determined that to get a

similar shimmer with paintings of clouded atmosphere, that I would need at

least 54 panels. With that knowledge, I headed for Sevier Lake on US Highway 50

stopping along the way to shoot fragments of the sky. It took around an hour to

arrive at the dry lakebed. When I got there, I photographed the ground and

highway as well. I had plans for several paintings.

When I viewed the 54 thumbnails of sky on the computer screen,

I had my doubts. It was a monotone mosaic of blue. Although light, the abstract

painting I was modeling it after, was full of all kinds of color. I decided to

go ahead with project. There is no real way to tell if an idea will work if it

is never executed. With a utility knife and handsaw, I cut all the materials I

would need to make the panels. In my spare time, I glued things together.

Because I’ve done a lot of framing, I know nothing is ever an exact match. To

compensate for that fact, the ragboard panels were cut a little larger than the

frames or platforms that they were to be mounted to. Sandpaper brought all the uneven

edges together. The practice of sanding was never anything I desired to

pursue, but because I make everything myself, sandpaper has become a constant

companion. Instead of dreading it, I just accept it as a key part of making art.

At any size, 54 paintings are going to require a lot of

time. Because of that fact, I decided to change the way I usually paint,

otherwise it would take a couple of years to complete. The work would have to be

a little more loose or painterly. With my experience as an abstract painter, I

learned to be open to what a situation desires. The scale of the project was

the equivalent of an unexpected drip. Listening to its direction changes what needs

to be done.

When I completed the first three paintings, I saw that all

the blue was going to be okay. Because many of the images were similar, when a

painting was finished, the corresponding photograph was immediately deleted to

avoid any confusion about what had or had not been completed. Being a framer, I

couldn’t help but frame a piece as soon as it was done. When originally

imagining the project, I saw all the framing in white. I had a handful of small

paint cans sitting around and decided to use the pale colors. Following that path,

the framing for the final piece would be an array of slight variations on taupe

or beige. The delicacy of the color scheme pleased me.

Having so many panels to paint gave me a chance to play

around a little. That was even in keeping with what I was trying to do. The

painting was intended to be about the beauty of randomness. Not having it front

of me now, I don’t remember all the different things I did. But beyond a

generalized looseness, there were some references to Pointillism that I really enjoyed

making. One of the more surprising pieces for me, was a painting of clouds that

primarily relied on the kind of lines I used when doodling in junior high

school. Even while using them, I could still be fairly discreet.

I started the piece in 2014. Working on it between other

projects, had gotten me as far 13 panels by the spring of 2017. Then I decided

it was now or never, and set everything else aside. Being able to delete a

digital image as each painting was finished was a good way to keep track of

progress. But, every time I counted how many images there were left to paint, I

felt overwhelmed. I looked forward to thresholds like I’m almost halfway there,

or there are only 19 panels left to go. The countdown helps. Over my career,

most of the things I’ve made were time consuming. Immediate gratification is

something I seldom experience. I get up each morning and go to work, and

somewhere down the line, much to my surprise, I’ll find that I’m almost

finished.

By the time I decided that it was now or never for the

project, most of the small paint cans that I mentioned before had dried out. I

planned to go to the hardware store and pick out some new colors, keeping with

the theme of subtle variation. After thinking about it for a while, I decided

to mix in a little acrylic with the colors that remained viable, that way there

would be a little more variation. In mixing the paint for one the frames, I

overshot a color and initially thought it was a little too intense. But rather

than repainting it, I decided to make a shift to the color scheme. The painting

was to be about the acumen of chance, and having a mix of colors could

strengthen that sense of randomness.

Part of the inspiration for this painting, came from an abstract

piece that I began 34 years ago. In it, all the squares are fixed, but because

there are 450 of them, a certain amount of randomness is inevitable. The sky

panels were painted individually so they could be moved around. Initially, the

configuration of the grid was the only restriction I had on their placement. I

liked the idea of not having a particular order in which to hang them. Going

for a form of randomness, none of them would have been numbered. But as I

thought about it, it was not hard for me to imagine some poor perfectionist

struggling to get them hung. How could anyone ever really know if they found

the perfect combination? I decided to take the stress away. I quickly laid

everything out on floor without much thought about where anything should go.

For anyone interested in creativity or design, that is part of the secret.

Don’t over think things. Being casual or relaxed gets you at least halfway

there. Standing on a chair, I began to move things around. When I saw a

configuration that I really liked, I stopped to number them. It is impossible

to ever know if my combination is the perfect one, but as far as I can tell, it

works absolutely well enough.

As I work, change often happens along the way. I thought I

was seeking randomness, but what I was really looking for, was the power of

chance to help me find or design something beautiful. In this painting, I

became like the nature that I rely on. You don’t have to figure out where the

sky panels are supposed to go. I’ve done it for you. That’s what nature has

always done for me. I never have to figure out where things need to be. I

simply look out at the land in front of me. Because of that fact, I’ve never fully

understood the concept of chaos. Everything appears to be related; even when

things seem to happen for no reason, randomness is a form of order. A

germinating seed becomes the weed that leads to a full blown forest.