|

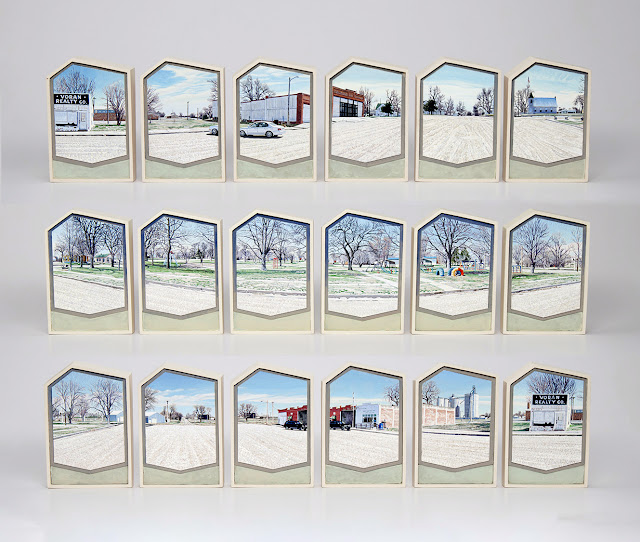

| Detail: The West Side of Hampshire Lane from Arapaho to Vernet, Richardson, Texas, October 1988, 10/17/96 mixed media diorama housed in 15 glassed in panels in 3 frames, 5 1/8 x 114 x 2 inches |

Around 1995, I

began to wonder if there would come a time when I no longer needed the diorama.

Although physical in nature, much of the depth inside was the result of plain

old painting. The following year, the diorama became new again, when I started

going through snapshots that had been stored away in an ice chest because there

were so many of them. The collection contained pretty much everything shot

while living in Richardson, Texas. My focus on the Dallas suburb had been

disrupted by roads trips and moves that eventually took me home to Fillmore,

Utah. Prior to then, I resided in the cities of Houston, Phoenix and El Paso.

The neighborhoods of each place, seized my devotion as though I’d grown up as a

local. That’s exactly why the diorama proved to be so effective. The formatting

of everyday terrain gave me a way to say just how much I loved my surroundings.

When the images were laid out across the floor, I saw that there was at least

ten years of work that I wanted to complete in two. To cover so much ground, I

would have to go small. I was living in Houston the first time I tried to make

a diorama as tiny as the photographic image that it came from. I never

understood just how minute the details could be until I tried to paint them.

Photography is such a common way of seeing that we’ve lost touch with what

distortion can really mean. We automatically fill in much of the missing scale

that would have to be there in order for a print or snapshot to be seen as any

kind of reality. In describing the veracity of a painting, how many times has

it been said that it looks just like a

photograph? It may seem like a strange thing to say, but photographic

imagery has replaced reality as a point of comparison. The success of a

painting is never measured against the splendor of the great outdoors. As I

tried to translate petite details into the making of a diorama, I discovered I

couldn’t do it. I didn’t have the chops or stamina to get it done. Over time,

the diorama grew ever more refined. Perhaps, it was that process that enabled

me to successfully complete a few miniature renditions of the format while I

was living in El Paso.

While in

Richardson, I shot numerous sprawling vistas of the city. Several swept away by

a desire to see the next connection, followed the panoramic swirl to unfurl 360

degrees of suburban habitation. With a conservative scale that made the

vertical side of a diorama just 8 inches high, those ocular accomplishments

spread out to be at least 10 feet long without ever trying. Imagine what 16 to 24

inches of verticality would do to a horizon. The latter measurement could easily

mean 30 feet or more of a suburban sprawl consuming the span of a colossal

wall. The length of a diorama was a measurement of time. Because of that fact,

I’d completed only one of them. With the reduction in size, I was able to

complete 5 or 6 of the fully surveyed portrayals of the city. Besides the

profile of the cutout and the sloped horizon, the thing that really made the

diorama work, was its dependence on the density of color. The much smaller

scale, made the compiling of color a less time consuming thing to do. A diorama

that had taken two or three months to complete, could be finished in a couple

of weeks. The reduction in size, made moving through my old neighborhood into

something that could be done.

The smaller scale

turned scrap into something that could be used. Because reflection free glass

was almost like gold, I couldn’t throw any of the fragments away. Instead, I

wrapped the pieces up so they wouldn’t scratch, hoping to find a way to use

them. Working with the bits of this and that, invited a kind of playfulness.

The parameter for many images was determined by the size and shape of leftover

glass. An insignificant piece of wood, to small or narrow to safety reshape

into a frame, suddenly became valuable. Something like a ¼ inch strip of plywood

with a ½ inch piece of matboard glued to the top of it, could be made into a

frame. Because structural materials were often not the same, something had to

be done to make the raw combinations compatible. Stained paper and wood simply

wouldn’t look very good. Paint was an obvious remedy. I discovered that brushed

on paint could be sanded into an exquisite finish. Although there was nothing

new in that, I never understood what it took to get it done. Because walking

was a constant part of my consciousness, I began to collect some of what I saw.

Bits of chipped and weathered paint, autumn leaves, sifted samplings of dug up

dirt, and the inside lining of bark from fallen trees became the veneer facing

for many of my put together frames. Working this way, meant there was less of a

need for a wood shop.

Of all the

miniaturized dioramas, The West Side of

Hampshire Lane from Arapaho to Vernet, Richardson, Texas, October 1988 was

likely the most decisive one for things to come. Inspired by the David Hockney

travel paintings that try to illuminate movement, the prospect of taking a

short journey filled me with ecstasy. Early on an October Sunday morning, I got

up to walk Hampshire Lane. With camera in hand, I chronicled all the buildings

on the west side of street with enough overlap to show that the photographs had

the same roadway in common. The distance from one image to the next involved

walking. The collection of snapshots documented travel. For the first time in

my life, a string of photographs didn’t try to seize upon the sweep of a fixed

horizon, and yet there seemed to be some kind of connection. Perhaps, that’s

because navigation is a function of sight. A vista is just suspended travel in

a continuous stream of visual sub consciousness. Because we’re designed to see,

we don’t perceive the entirety of the data crush that makes getting around so

easy. The primary reason I enjoy travel by foot or car, is that it takes me to

a place where continuously shifting vistas obliterate the compositional conceit

of thinking that beauty is so rare that it needs to be dug out to be found.

The West Side of Hampshire Lane… united 15 separate scenes in a frame that

was divided into three sections. Those divisions were made for the sake of

handling. Between each scene there was a space that opened up to the wall. The

serial configuration of buildings along the street was repetitive enough to

form a kind of horizontal laddering that was reminiscent of a filmstrip.

Although not part of the thought process, the fact that the combined images

recorded a short journey, meant that the framing turned out to be a perfect fit

for the depiction of travel. A roll of chronological stills is how movement is

recorded. Without knowing it, the sequencing of individual images would eventually

become the primary way of portraying panoramic scenery. The depiction of a

vista as a singular event never really existed. The span of any horizon always

required movement from the camera. Even while eyes scan the breadth of a

horizon, seeing renders the fragmentation of sight as a complete picture. The

camera can’t do that. The viewfinder can only know frozen moments. It can’t

comprehend time as continuum. Although the diorama closely resembled what we

think we see, that link was missing. Of course, I didn’t know any of this at

the time. That would come later on, when I tried to align some overlapping

photographs that refused to go together. When I pulled them apart, the

separation revealed an interlude that I hadn’t noticed before. The walk along

Hampshire Lane foreshadowed that knowledge in format and framing. The division

or intervening pause meant that paint could showcase more than a frozen moment.

Although the illustration of time was still made of stills, the collection of

more than a single moment represented a measurement in time. Partitioning

breaks within the framing, recorded the passage of time like the demarcation of

tree rings. We can see the representation of place as a cross section in time,

however fleeting a scene may be.