|

| King Mountain Road |

|

| Abandoned Service Station, Grandfalls, Texas |

|

| Grandfalls Union Church |

|

| State Highway 329, Grandfalls, Texas |

Just out of college, I moved to Dallas from Reno, Nevada in

1983. In Reno, the presence of the Sierras permeated everything. Because of

that fact, errands never seemed routine. Suddenly stuck in a big city, I spent

a lot of time on the highway, searching for the exhilaration of mountains. The

weekend pursuit of higher places in variations of the Hill Country proved

elusive. The vistas found a couple hundred miles out of Dallas, seldom surpassed

what could be seen from overpasses and parking lots.

In 1985, my brother Steve and I headed for the Guadalupe

Mountains. Examining a map, I realized that an indirect route would enable me

to see more mountains. Instead of heading west towards Fort Worth and Abilene,

I veered out of town in a southwesterly direction through Midlothian, Cleburne

and Glen Rose on U.S. Highway 67. Somewhere before Santa Anna, the ability to

see the countryside was enveloped by the arrival of night. We stayed in San

Angelo.

In the vistas beyond San Angelo, navigation seemed to end. It

felt like driving off the edge of Texas. The highway hadn’t lost its way, but

the indiscriminate valleys and elongated bluffs and ridges from the previous

day were gone. Although the land wasn’t flat, the features of erosion meandered

away without incident. Because of that fact, the towns of Mertzon and Barnhart loom

large in my imagination. I’d never seen terrain like this before. Juniper and mesquite

trees peppered slopes and hollows that aimlessly furrowed away the line of the horizon.

Unlike on the plains, or in the mountains, the gravitational pull of drainage

had no visual threshold. It was a land without horizons. Without the orientation

of a base line, driving was just the emergence of more earth and sky. Although

I had never been to Australia, the Outback came to mind. And although I was traveling

to see the mountains, the area between San Angelo and Big Lake left an

indelible impression on me.

Without the consideration of sky, Texas can feel pretty

small. While the woods, prairie, hill country and plains are not the same, within

each region, the vistas are limited. You can’t see very far. And, there’s not

likely to be anything on the horizon to indicate where you are. Navigating by the

sight of a distant silo is like shadowing the buoyancy of a cumulus cloud. You’re

going to be completely lost without the aid of highway signs and markers.

Although my visions of the Outback are tied to the area

around Barnhart and Mertzon, on further consideration, the sensibility of

feeling lost could apply to almost any place in Texas. Frequently, there is no

distinguishing feature on the horizon. If there happens to be a bluff, isolation

is the only feature that makes it significant, because so many of the bluffs in

the state seem to be so much the same. U.S. Highway 380 wanders through the

Brazos River watershed on its way to the horizon. On the south side of the

highway, somewhere around Aspermont, Double Mountain comes into view. Stopping

at a picnic area for a better vista, Double Mountain quickly becomes obscured

by mesquite trees and weeds. Better views almost always prove elusive. Destination

lacks satisfaction. It comes without a sense of arrival.

In 2010, I was heading home from a family visit in Utah. Exploratory

mileage took me all over the place, including Sitting Bull Falls, 40 miles west

of Carlsbad, New Mexico. On the way out, I followed gravels roads down and around

the western edge of the Guadalupe Mountains. It was dusk by the time Guadalupe

Peak and El Capitan came into view. I was glad to see the gravel road graduate

to pavement. Traveling south through brush, sand dunes and salt flats, the road

terminated at the highway. Out of the valley, U.S Highway 62/180 is a steep

grade to the top of Guadalupe Pass. From the other side, it doesn’t seem like a

pass at all. There is a reason for that. Although Carlsbad at 3,127 feet above sea

level, is lower than the 3,730 foot elevation of Salt Basin directly below the

summit, coming from Carlsbad, it takes 57 miles to scale the 5,424 foot pass.

Within that mileage, the land and mountain range gradually ascend in a southerly

direction. It is only at the tail end of the range that the Guadalupe Mountains

eclipse a riddle of rolling hills and shallow canyons. Initially, there is

little to separate the range from the erosion of the elevated plains, which

drain the eastern flank of the Sacramento Mountains. But the head, which is

also the termination of the range, ascends with such force, that the remaining

peaks frame an absolutely amazing national park.

Near the New Mexico state line, RM 652 came into view. Since

it was dark, I couldn’t really appreciate the nearly 60 mile drive to Orla,

Texas. Other than the stars, there wasn’t much I could see. The restricted

vision of headlights, seldom outshines the lines on a highway. Outside, the

night was a mystery of crickets. On Texas backroads, the letters FM on a highway

sign signify Farm to Market. However when the land turns desolate, grazing

replaces the rotation of crops. Through vistas of mesquite, cactus and brush,

the letters RM stand for Ranch to Market. Because I’d been this way before, I

knew what the land was like even in the night. The road rolled through erosion

and low lying hills. A pale spectrum of greens, mesquite, creosote, yucca and

cactus, partially concealed the bleached surface of the earth. Pump jacks and

cattle foraged under the flank of continental sky. Far west Texas is the

atmospheric divide between brilliant skies and the muted blues that dominate

much of the country. Almost like water seeking its own level, moisture moving

up from the Gulf of Mexico, fans out across the nation east of the Rocky

Mountains. The boundary between air masses is not fixed. Traveling west,

sometimes you’ll find that the atmosphere in Amarillo is absolutely clear.

Sometimes the sky doesn’t begin to sharpen up, until you hit San Jon, New

Mexico. The fluctuation of sky, could almost be thought of as a tide. The

American scene east of Amarillo, lies under the prevalence of shallow skies.

As with anything outside the West, it took time for me to

appreciate the washed-out skies and the prematurely blued horizons. Although I

wouldn’t have described it like this at the time, the high concentration of blue

in vistas of the immediate countryside, seemed like seeing a roll of poorly

exposed photographs. The light just didn’t feel right. The limited visibility,

left the land feeling bland and closed in to me.

Once I got to Orla, which wasn’t much more than a junction, U.S.

Highway 285 headed in a southeasterly direction for the town of Pecos. Exhausted,

I stopped for the night. But by sunrise, I was ready to go. Instead of craving

the ease of Interstate 20, the only rational way of traveling back to Dallas, my

hesitation began to swell on the overpass spanning the freeway. When the left turn

for the onramp arrived, I kept driving. Not far out of town, a left turn off

U.S. Highway 285 introduced me to FM 1450. The highway designation of FM 1450 sounded

like the tuning position for a radio station. However, I enjoy the silence of

driving. I’ll take the rhythm of spinning tires on asphalt over the airwaves of

a playlist most any day. Nothing beats the reverberation of an isolated highway.

The direction I was heading, would have put me on Interstate 10, around 20

miles south of McCamey, eastbound for San Antonio, if the road didn’t end at FM

1053. But before I hit the termination of the road, I turned north on State Highway

18. The scenery remained the same. Hardscrabble greens chased the edge of horizon.

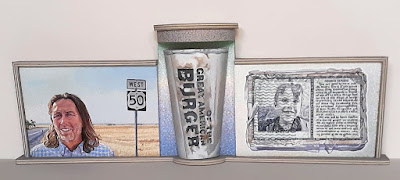

In Grandfalls, a right turn at 1st Street became State

Highway 329. Like so many out of the way places, the town had seen better days.

Deserted service stations framed the western corners of the intersection. One

was surrounded by oxidized vehicles. The other was overcome by an onslaught of

weeds. Christianity occupied the two remaining corners of the intersection. Grandfalls

Union Church, built in 1910, stood on the north side of the highway. On the

south side of the highway, The First Baptist Church was pastored by the

Reverend John (Buck) Love.

I have no descriptive memory of Crane. I don’t even remember

the intervening mileage between Grandfalls and Crane. But I am certain that the

indiscriminate splendor of the highway would resurface, if I hit it again. Repeated

mileage fosters a kind of expectant recollection. Highway driving reveals a

perennial past. Recognition of the edge of town happens as soon as you see it

again.

Beyond Crane, I saw a sign for King Mountain Road. Driving

down the highway, an alignment of bluffs framed the views to the west in a

southerly direction. All of them seemed to be of similar elevation. I wondered

which one of the flattops was King Mountain. If I’d been able to see the bluffs

from above, I would have understood that what appeared to be a progression of

bluffs was just the outside perimeter of a large mesa. King Mountain was not a

mountain at all. If you’d never been anywhere beyond the top of King Mountain,

you would have seen the earth as continuous plain, until you discovered that

there was an abrupt edge to your surroundings. Living on a flattop in the sky,

the land below had been impossible to see. You couldn’t have known that you

shared the clouds with unseen horizons. Until then, your fear of heights

couldn’t exceed the length of your shadow. The discovery of abyss shattered the

expanse of flatness.

Although I momentarily headed in the right direction earlier

in the day, I wound up in McCamey, not far from Interstate 10. When I left

Pecos at sunrise, I had no idea that I’d be going home on U.S. Highway 67. But

a series of backroad decisions, led to a northeast trajectory back to Dallas. The

last time I headed in this direction on Highway 67 was in 1988. The trip back

from the Guadalupe Mountains was an adjustment. I’d spent a week living in slow

motion. In places, the power grid was limited to a single strand of wire strung

from nothing more substantial than juniper posts. Within a day or two of being

out there, it was no longer clear what day of the week it was. The nice thing

about the highway is that it slowly angles its way back into the heart of the

city. Arriving at San Angelo is like a leaving a featureless sea. Although the topography doesn’t pack much of a punch, the staggered bluffs and valleys support farming. Muted

blues and greens of distant ridges frame the fields and trees along the

highway. The small towns and the rural countryside come with increasing traffic traveling towards Dallas. Late at night, the headlights of Cleburne can be just too much.

Because for several days, I experienced a nighttime circumference of stars, I had to

white-knuckle my way back into the city. The bright light stimulation of moving

cars came with an anxiety of dying.

So many years ago, as the sun began to set, a traveling Carnival

illuminated a field of parked cars at the edge of town, somewhere along U.S.

Highway 67. I don’t know why I didn’t take a picture. While it could have made

a great painting, sometimes the most impactful impressions continue on precisely

because there’s no remaining evidence. The camera would have likely reduced the

moment to a snapshot. There’s power in abstraction. Twilight never ends envisioning the outlines of the Ferris wheel against the sky. Perhaps that is the lure of Texas. The features

and scale of the place prove elusive.