Thursday, October 1, 2020

Thursday, April 16, 2020

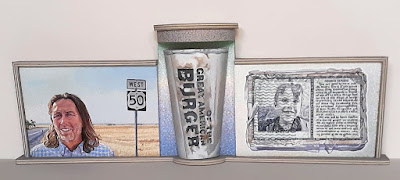

Martin Avenue, Stafford, Kansas, U.S. Highway 50

|

| Martin Avenue, Stafford, Kansas, U.S. Highway 50 acrylic on six shaped ragboard panels, artist-made frames 12 5/8 x 60 1/4 x 2 3/16 with a 2 3/4 inch spacing at the base of each frame |

The view of Martin Avenue, Stafford, Kansas comes from a trip taken in 2013. I was in Dallas for the opening of The Dallas Years, a show intended to commemorate the time I spent living in the city. On the way home from Valley House Gallery to Utah, I headed north on U.S. Highway 75.

Because I went to the Dallas Museum of Art before I left, it

was perhaps early afternoon, before I cleared the outer reaches of the city.

The journey into Kansas, is an all day trip. In the later part of March, the days

are not long enough, without an early start, to cover any distance without

driving into the night. I’d been informed by a gallery staffer, that a huge

snow storm blew through Kansas. Ignoring the warning, I assumed that the roads

would be clear enough, by the time I reached Emporia, where I planned to spend

the night.

Seeing any part of the eastern side of Kansas, happened so

long ago, that I really looked forward to the excursion. An old friend of mine,

who became my wife, and then ex-wife, was going to school in Lawrence at the

time. The year was 1988. When I went to see her, I’d leave on a Friday just after

work. Because it was late in the day, the sun always set before I got to Kansas.

The countryside vanished into a line of oncoming headlights, long before crossing

the bridge over the Arkansas River into downtown Tulsa, Oklahoma. Because it

was late, beyond the Kansas border, most travelers had already retired for the

night. Highway miles would slip away, with the headlights of a single car, riding

a fixed position, a far-off reflection, centered in the abyss of my rear view

mirror. In the dead of night, it was not hard for me to envision, something

from a movie scene playing out in real life. Then I’d breathe a sigh of relief,

when the headlights left the highway, headed in the direction of some late

arrival, buried deep within the quiet hours of starlight.

Until I drove home on Sunday afternoons, I never got to see

Kansas by daylight. Although the state is still part of the plains, the

countryside seemed less stubby than either Texas or Oklahoma. Memory is a vague

kind of thing, an impression of events with most of the details missing. Retracing

the mileage of any highway, fills in with bits of familiar information. The succession

of events, recovers all the missing details that quickly vanish chasing down

whatever lies just behind a receding horizon. Every oncoming mile, becomes

knowledge based anticipation. Remembering previously seen sites, is played out in

a recognition that comes from the motion of momentary photographic memory. I

find, that I remember all the insignificant bits of a trip that time had

forgotten.

When I pulled into Emporia, the night air was as brittle as

the plowed up snow that surrounded the motel. Because I was late leaving Dallas,

I never got to replay the familiar sights of the Kansas countryside. In the morning,

heading in a westerly direction, every mile of horizon on U.S. Highway 50 would

be new, until I got to Colorado.

By the time I got to Stafford, I’d traveled nearly a 150

miles, taking pictures all along the way. Although primarily a two lane road, the

current highway bypasses most of the towns of Kansas. If you hope to see anything

affiliated with Main Street, you will need to leave the highway. The pull of

the horizon, is punctuated every ten miles or so, by a colonnade of white silos.

Travel any distance and you’re bound to witness, a freight train overtaking the

fortress of a grain installation overseeing the plains.

The waning Martin Avenue, may feel like the perfect combination

of clutter, a rare something that I’d come upon, that was just waiting to be

painted. Standing in tracks of gravel, it is hard not to see many things that

register as canisters of the past. There is the profile of silos. Piles of new

and used tires, anchor the fluting of a metal shed, which intrudes into the

view of a deserted service station. Behind it hide, a couple of old houses

weathered nearly all the way to gray. There is a classic car, that has become

such, by surviving the ravages of time. There is the back end of a pickup truck,

which has become a homespun trailer. The front windows of a pink clapboard

house, with a handicapped ramp and railing, are covered over in tinfoil. A blue

sky of thinly veiled clouds, lends to the sensation that the place is barely

hanging on, not quite ready to surrender to the shade of silence that echoes

across most any horizon. I guess it could be easy to believe, that this scene

was a lucky find, but a ballad of loss, can be found anywhere. I know this from

walking. If you’re open to the nature of place, there is a story ready to

unfold.

I happen to be fond of architectural form, whether it be the

lift of a high-rise condominium, a picture frame that sharpens the breadth of a

painting, or the inverted shape of a tapered paper cup, that is all about

volume and circumference. Even a blank sheet of paper, feels complete to me. I

see no separation between the artwork and the surface that supports it. Picture

plane and paint are both significant. Within the panels of Martin Avenue, I

wanted to get away from the constraint of vertical rectangles. I didn’t want

the sequence to hang as pillars of 2-dimensional space. The shape of a

rectangle amplifies the impression of a plane. It is difficult to experience a sensation

of space within the confines of a shape so stable. The squared up framing of information,

resists the influence of horizontal spin and the impact of gravity. The

rectangle offers no possibility for periphery, or a chance to be distracted.

Without the sweep and dive of perspective, it is hard to know where you are.

Imagery becomes a flat abstraction, a postcard kind of a thing that can’t be

inhabited. The perception of space is dependent on a perspective that is hard

to achieve within limitations of a standard rectangle. That is why when I

photograph a place, the process almost always involves more than just one

picture.

The panels were designed to amplify sky. However, they happen

to point in every direction. Although the shape favors the pitch of the rooftop

and the angle of the left corner, the structure also leans to the right,

encouraging you to repeatedly take in every direction. That bit of visual

wanderlust embraces the nature of place. You no longer remain a spectator

outside the picture plane. The depiction of a moment in time, begins to take on

a note of recognition that hopefully extends a little beyond the limits imposed

by 2-dimensional space. I hope the painting has a presence, a sense of

atmosphere, close enough to provoke a feeling of kind of like being there. And

if you happen to know this sort of place, the landscape, much like a song,

becomes your narrative.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)