Perhaps, Belpre can best be described as a small town around

20 miles east of Kinsley, Kansas. That in and of itself is not much of a

description, but since I’ve driven the highway, I know that Kinsley, Kansas is Midway U.S.A. There is a sign there with

arrows pointing in opposite directions to New York and San Francisco. From that

location, it is 1561 miles to either city. There is a roadside park with a black

steam locomotive, picnic tables, and a small museum. I considered the mileage

posted on the large painted arrows and without much thought decided to remain

on the open plains for a little while longer.

As a proponent of the long view, I drove the length of the

nation and saw only a few sites that could be described with a single snapshot.

Without at least two consecutive views, it is hard to capture the idea of

place. If you only shoot the barn, you have no field to tie the structure to

the horizon. If you shoot only the field, there is no element to measure the

distance between weeds stranded in clods of dirt and the sky. Without a sense

of place, an image no matter how beautiful it may be is always a bit of an

abstraction.

When I pulled into downtown Belpre, the first thing I saw

was the abandoned real estate building. Looking at the surroundings, it was not

difficult to see that business had been rough. The streets had been reduced to

a covering of sandy gravel and commerce was limited to the US Post Office and

another building that may have been a bar. On the other side of the street,

there was a park with a painted playground in a field of trees that pretty much

concealed the water tower. From that spot, there were also views of grain

elevators, a steel building, a rutted country road, houses, a church, a

building with no identifiable store front, and the possibility of an apartment

building. I had come to capture the American scene; everywhere I looked it

surrounded me, there was nothing to do but shoot everything I could see.

Because of the height of the trees, I shot the expanse with the camera held

vertically. I frequently go long, and there is always the option to shoot a 360

degree view of any location, but rarely is it imperative to capture the essence

of a place. I’ve always liked parks and cemeteries. Often, they are the only

visible things holding a town together. Once they go, a town is bound to be

nothing more than crumbling rubble along a highway.

My father liked to camp and travel. As a child, I was only

interested in mountains. The habitation of in-between places bored me. When I

moved to Dallas after college, I was a long way from Saturday drives up into canyons.

In the isolation of the big city on the plains, there was no way for me to

connect to the nature I loved without several days of vacation. I had to learn

to see other things. That separation from the mountainous West was the best

thing to ever happen to me. In the absence of what can easily be identified as

nature, I began to see cracks in the sidewalk and sky. Nature went from being

the scent of tall pines on a mountainside to the idea of being there. As long

as you are still living, you can connect, and that connection may be the

storefronts of a shopping center, a barn, or vacated real estate building 20

miles east of Kinsley, Kansas. The moment was the thing I learned to really see

and appreciate.

In 2005, I began painting the Nevada section of US Highway

50 known as the Loneliest Road in America.

It was a familiar highway; my parents divorced when I was a child; 500

miles of mountains and valleys separated them. School years were spent living

in rural Utah with my mother. Summertime took us to Reno, Nevada to live with

my father. With the exception of a couple of years, I’ve been painting the highway

ever since 2005. I expanded the survey in 2014 to include the entirety of the highway

from Maryland to California. A vast project, it is not something that can be

completed in a single season. It will likely require the rest of my life. I

like the idea of covering the breadth of the nation from the vantage point of a

single highway. A theme without limitations, I see the highway as a kind of a

clothesline to hang innovation on.

When I moved to Dallas in 1983, I took a job as a picture

framer. It is a skill every artist should have given that it is a large part of

the material cost of making art. Over the years, I’ve done some innovative

framing, but it would be a mistake to think it was driven by the frame shop

experience. I started painting when I was ten and was pretty confident in my

ability, but I didn’t realize that I was creative until I hit college. I had

become disenchanted with landscape painting and latched onto abstraction. That

is the thing that saved painting for me. Being able to respond directly to what

was happening on the canvas taught me that anything was possible. If anything

was possible, then any box could be rethought or imagined. In the embrace of

abstraction, I acquired the thinking skills to remake the landscaping painting I

grew up with as a child. I could learn to paint the moment which is what I did

when I started making dioramas of my neighborhood in Richardson, Texas. Of

course, it wasn’t that straightforward. It never is. As an artist, you can’t be

standing at point A and look out into the distance at position B and think

“that looks pretty nice, I think I will go over there” because the beautiful place

called B doesn’t exist until you create it, and that can’t happen without a

willingness to leave part of your identity behind. You can never realize who

you really are by remaining in the same place. While you may have some ideas of

where you want to go, vision is not about culmination.

An initial drawback of the diorama was that it was housed in

the structure of a shadow box and a shadow box casts a lot of shadow. My

solution to reduce unwanted shadow entailed parting ways with the structure of

the frame. That meant that in the entire framing industry, there were no

moldings that I could use. At that point, I would have been better off if I’d

been a cabinet maker. If I’d been one, perhaps I could have imagined a better

solution, but even so, the one I came up with hung nicely on the wall and

changed the relationship between the art and the frame. The two were no longer

separate things to me. The diorama made painting a kind of architecture, and

although I no longer make dioramas, I continue to see painting that way.

Four years ago, I woke up one night with an image of a

concaved surface that leaned forward in my mind. If it came from a dream, I

don’t remember it. A few years earlier when I left framing, I replaced my table

saw, scroll saw, chop saw and router with a plastic miter box and handsaw.

Speed is not everything. It eliminated a lot of noise and I could work

anywhere. Also, there was the added satisfaction of knowing that my hands were basically

safe. The structure I imagined would have required a lot of the equipment that

I’d gotten rid of. I decided that what I wanted to do could be done using

ragboard. The solution was a typical one. I always seemed to find a way to

innovate within the confines of the situation. Building the structure out of

layered ragboard really was the best solution; acid free paper isn’t going to

crack with age, as wood has the habit of doing.

Once a shape is imagined, others come to mind. Although I’d

already painted a couple pieces with pitched rooflines, I wanted something that

was asymmetrical. I covered the laptop monitor with a window cut out of

cardstock and made adjustments to it until I found the right angles. I liked

what I saw. The asymmetry felt more dramatic. The sensation was a little more

like being outside. The view was less fixed or stable. It is all too easy to see

a rectangle as a plane. Although no longer a rectangle, the shape was still a

plane. The tilt forward forced a sense of direction into the flatness of the

panel. Even though the positioning moved in the opposite direction of the

perspective I was trying to illustrate, conceptually it was the right way to go.

Perhaps that sounded a little confusing, but if you look at what I’ve done, you

will see that the sky is literally closer to you than the gravel of the street.

Although overhead sky can never be reached, in a sense it is very close to us. When

walking down the street, we never see our feet, making the connection to earth more

distant than the drift of sunlit clouds in a shifting atmosphere.

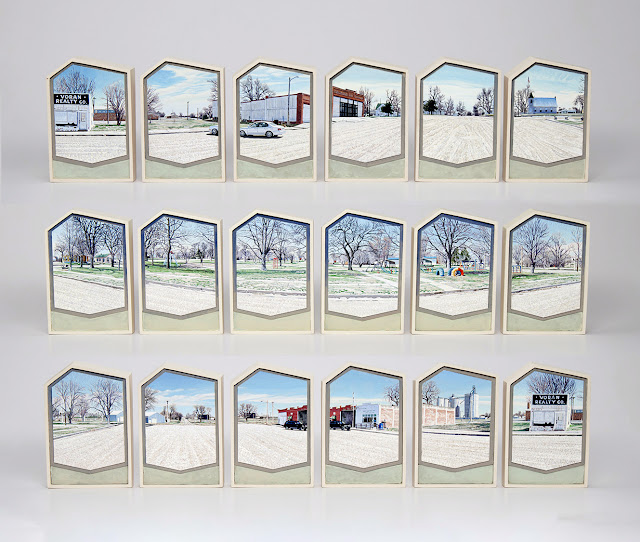

The pitched roofline was fairly new when I decided to paint

downtown Belpre, Kansas. I had painted just one of the asymmetrical variations

before and it was on a horizontal panel. I wondered how a vertical version of

it would work, and to answer the question I settled on a symmetrical sweep of

18 asymmetrical panels. A 360 degree view of a place has no fixed beginning. As

long as the images are in sequence, you can start any place, and every time

that is done the composition changes. Before the digital camera, I painted from

photographs glued to matboard. I knew what the composition was going to be

because I had joined everything together. If Belpre was a painting from back

then, it would be a single panorama where everything was joined. I worked that

way for years, and then one day tried to overlay photographs that didn’t want

to align. When I pulled them apart, I liked being able to see them individually

and how they related to one another at the same time. The separation retained

an element of time that the joined image concealed. With the panorama it was

easy to believe that you were looking at a frozen moment instead of a

collection of them. The separation of the photographs was a better reflection

of what I saw. The place wasn’t seen all at once. It took time to assemble the

slanting of a horizon. I don’t think that a panorama made of separated images

is better than one where the separation is removed. Whatever can be achieved is

never going to be exactly what we see. Now that I know that there are at least

two ways to view the horizon, I use both of them. I enjoy being able to look at

things in new ways, and the new way really suited the 18 panels I chose to use

for Belpre, Kansas.

Working from a monitor is different. Since I no longer print

anything out, I’ve skipped a step. The completed painting is the same kind of

surprise that I used to get when I aligned the photographs into what

essentially was the sketch for the diorama. It’s interesting that the sequence

I shot of the street just happened to be symmetrical. I could have started with

the camera anywhere, and anywhere else it would not have been the same. Of

course, I could have moved the sequence around until I achieved that balance.

But, I painted the panels in the exact order that I shot them. I find that on

some level to be really surprising. That was always the exciting thing about

gluing the photographs together. Looking through the view finder, I never knew

exactly what I had until the negatives became prints and they were joined

together.

I am as surprised as anyone by the painting. Since I had

never painted anything like this before, I didn’t know what the repetition of

the pitched edges would look like hanging on the wall. Cheryl Vogel of Valley

House Gallery in Dallas, told me a visitor saw a picket fence kind of thing in

the configuration. I can also see that, but I never really knew what the

individual panel would look like when it was repeated 18 times, particularly

because I was building the panels at the same time I was painting them. That is

part of the reason for making art. You can never be sure of what an idea will

look like until you make it a physicality. I can see a picket fence kind of

thing in the structure, but I also see the possibility of headstones. Both

images are appropriate when thinking of small towns. One appeals to the safety

of knowing your neighbors and all the things that go with small town living,

the other considers the difficulty of trying to maintain a community outside the

economic engine of the city. After having driven the length of US Highway 50, I

am not hopeful about the fate of many of the in-between places. Having a small

college nearby seems to help, as does having all the historic buildings intact.

But even in the ruins of small communities, the romantic side of me has always

seen a kind of richness out in the places where there is still room for a view.